A bibliography of books and papers by Penelope Walton Rogers

published since the establishment of the business in 1980

Popular magazine articles, editorials and book reviews have been omitted.

Penelope Walton became Penelope Walton Rogers in December 1990.

For bibliographies for other authors, click on the links to the right.

Some of these publications can be downloaded from Pangur Press

and others from Academia

2021

Walton Rogers, P, 2021. 'In search of Hild: a review of the context of Abbess Hild's life' in G R Owen-Crocker and M Clegg-Hyer, Art and Worship in the Insular World: Papers in Honour of Elizabeth Coatsworth, 121-153. Leiden: Brill.

2020

Walton Rogers, P, 2020, ‘Chapter 12. Non-ferrous metalworking networks in Scandinavian-influenced towns of Britain and Ireland’ in S P Ashby and S M Sindbæk (eds), Crafts and Social Networks in Viking Towns, 251-283. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow.

Walton Rogers, P, 2020, ‘Chapter 5. Textile networks in Viking-Age towns of Britain and Ireland’, in S P Ashby and S M Sindbæk (eds), Crafts and Social Networks in Viking Towns, 83-122. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow.

2019

Maeder, F, Walton Rogers, P, and Gleba, M, 2019, ‘A mysterious little piece: a compound-weave textile incorporating sea silk from the Natural History Museum, London’, Archaeological Textiles Review, 61, 114-121.

Walton Rogers, P, 2019, ‘Costume and textiles at Barrow Clump Anglo-Saxon Cemetery (2003-4)’ pp251-5 and ‘A note on mineral-preserved textile on shield grip (Grave 2915)’, pp257, 259 in P Andrews, J Last, R Osgood, N Stoodley, A Prehistoric Burial Mound and Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Barrow Clump, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire (English Heritage and Operation Nightingale excavations 2003-14) (Wessex Archaeology Monograph 40). [Some of the textiles from the 2012-2014 excavations were reported separately by E Cameron.]

2018

Walton Rogers, P, and Greaves, P, 2018, The Ties that Bind: Fur-Fibre Cordage and Associated Material from Dorset Palaeo-Eskimo Sites in Eastern Canada

Over 160 finds of cordage made of white animal fur have been recovered from excavations of Dorset Palaeo-Eskimo sites in the vicinity of Baffin Island, eastern Canada. Almost as many fragments of animal pelts and loose fibres have been excavated in the same sites. This report describes the structure of the cords and the appearance of the pelts, but the main emphasis is on the identification by microscopy of the fur fibres. The evidence shows that while a wide range of wild species was available as pelts, the coat of the Arctic hare was the primary source for cordage, with Arctic fox fur as a significant contributor. A selection of comparative material from Norse and Inuit sites in Greenland has been included. The study was carried out on behalf of the Helluland Archaeological Project. Available for download at Pangur Press

Walton Rogers, P, and Thompson, M, 2018, 'Chapter 7. Gender and costume in the Merovingian Cemetery at Broechem, Belgium', in R Annaert, Het vroegmiddel-eeuwse grafveld van Broechem/The early medieval cemetery of Broechem, Vol 1, 132-71 and Vol 2.passim. Bonn: Habelt.

Walton Rogers, P, 2018, ‘From farm to town: the changing pattern of textile production in Anglo-Saxon England’, in A Ulanowska, M Siennicka & M Grupa (eds), Dynamics and Organisation of Textile Production in Past Societies in Europe and the Mediterranean, Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, Fasc.31, 103-114. Łódź: Polish Academy of Sciences.

Wild, J P, and Walton Rogers, P, 2018, ‘Creature comforts at Vindolanda: two unique wool mats with knotted pile’, Britannia 49, 323-333.

Walton Rogers, P, 2018, ‘Bedding’ (p322), ‘Carved bed head ornament’ (pp322-7) and ‘Textiles and other organics’ (pp331-2), in C Evans, S Lucy, R Patten, Riversides : Neolithic barrows, a Beaker grave, Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon burials and settlement at Trumpington, Cambridge (McDonald Institute Monographs: New Archaeologies of the Cambridge Region, 2). Cambridge.

2017

Walton Rogers, P, 2017, ‘Textile analysis’ pp 109-110 in Daniel Rhodes et al., ‘Cist behind the Binns: the excavation of an Iron Age cist burial at the House of the Binns, West Lothian’, from Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), 103-112.

2016

Walton Rogers, P, and Rackham, D J, 2016, ‘Bone and antler artefacts’, pp53-5 and ‘The buckle loop’, p57, in S Paul, K Colls, H Chapman, Living with the Flood: Mesolithic to Post-Medieval Remains at Mill Lane, Sawston, Cambridgeshire (a Wetland/Dryland Interface. Oxford: Oxbow.

A small number of finds, mostly of bone and antler, were recorded from sunken-featured buildings in an Early Anglo-Saxon settlement at Sawston Mill Lane. Sawston is a multi-period site in the valley of the River Cam. Two beads have been described by Cecily Cropper and the more abundant pottery by Sue Anderson.

von Holstein, I C C, Walton Rogers, P, Craig, O E, Penkman, K E H, Newton, J, Collins, M J, 2016, ‘Provenancing archaeological wool textiles from medieval northern Europe by light stable isotope analysis (δ13C, δ15N, δ2H)’, PLOS ONE Open Access, October 20, 2016. For full paper click here

The isotopic composition of keratin in wool textiles and collagen in sheep bones from archaeological sites in Britain, Iceland and northern Germany was examined, and compared with modern samples. The light stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen and non-exchangeable hydrogen, which in broad terms relate to temperature and rainfall, were used. Most results for wool and bone, past and present, proved to cluster by geographic location and statistical outliers could therefore be interpreted as of non-local origin. Decay during burial in waterlogged conditions did not appear to obscure the results. Isotopic variation caused by environment and farming practices was also considered.

For the Icelandic site of Reykholt, the results showed a clear distinction between the textiles identified on technological grounds as probable imports and those likely to be Icelandic products (see Walton Rogers 2012, below). The two most easily identifiable Scandinavian-style textiles from York, the vaðmál-like twill and the ‘Coppergate sock’ (Walton 1989), were made from wool that isotopically came from a climatic band stretching from Ireland (including Viking Dublin), through Britain and into Denmark (including Hedeby), while northern Scandinavia could be excluded. Only one sample from York could be attributed to northern latitudes. More surprisingly, an early15th-century knitted fragment from Newcastle upon Tyne (Walton 1981), which was made of a Fine fleece-type and dyed with kermes (insect red), proved to be made from wool that originated in Britain, northern France, or somewhere with a similar climate. Italy or Spain, which had previously seemed the most likely place of origin, could be excluded. Textiles from Hessens (Wilhelmshaven, northern Germany), proved to include outliers of uncertain origin, suggesting long-distance exchange.

2015

Walton Rogers, P, 2015, ‘Textiles and animal pelt’ p134 and ‘Costume and soft furnishings’ p211 in C Fern, Before Sutton Hoo: the Prehistoric and Early Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Tranmer House, Bromeswell, Suffolk, East Anglian Archaeology 155. Bury St Edmunds: Suffolk County Council.

The Tranmer House cemetery lies 500 metres north of the famous ‘royal’ mound burials at Sutton Hoo. It is a flat cemetery, but the well-furnished graves, including at least two with swords, and certain similarities in burial practice, make it a likely predecessor to the later mound burials. The area excavated yielded over 30 inhumation and cremation burials, most dated to the second half of the 6th century. The 29 recorded textiles were mainly from male-gender graves and proved to be typical of the 6th century. The three phases of the site demonstrated the gradual change from ZZ to ZS 2/2 twills noted elsewhere. Of particular interest are two examples of 2/1 twill in linen, one a fine fabric wrapping a metal bowl; a heavy wool textile, possibly a coverlet weave seen elsewhere in Suffolk; and a linen tape binding on one of the swords. In the male-gender graves there were wool diamond twills, perhaps cloaks, laid over and/or under the body; three examples of animal hide; one, possibly two, feather-stuffed pillows; tabby repps perhaps used for cummerbunds; and a yew-wood belt. The four female-gender burials with preserved textile included a woman who belongs to a distinct group, tentatively identified as cunning women (see Boulter and Walton Rogers 2012, Flixton, below), from the presence of an extra pouch, a collection of amuletic curios, a trio of strap-ends and the dominant use of amber in the necklace.

Walton Rogers, P, 2015, Dyes in textiles from Schloss Tirol, Italy’ pp63-4 in B Nutz, Gerüstlöcher als Tresore für Archäologische Textilien (Fori Pontai come Casseforti di Stoffe Archeologiche), Landesmuseums Schloss Tirol Publication Vol.6 Part 6. Schloss Tirol. The main report has parallel texts in German and Italian, the dye report is in English.

The textiles from Tyrol Castle were found stuffed into the cavities in the masonry that mark where wooden walkways and stairs were once attached to the interior wall of the crypt. Most of them seem to date from the 14th century, at a time when the crypt was used as a strong-room. As described in the catalogue by Beatrix Nutz, they include fragments of a studded brigandine of yellow silk with red linen lining; other dyed silks of different weaves; a silk and gold patterned tablet-woven band; cords and skeins of yarn; and remains of a textile standard with a design in gold-leaf. Amongst a small number of finds from other parts of the castle there is some post-medieval metal-thread lacework. The dyes identified by PWR were kermes (‘grain’), Polish cochineal, lichen purple (‘orchil’), dyers’ madder, weld, woad/indigo and tannins. These results were related to archaeological and historical evidence for dye use in late medieval Europe.

Rogers, N, Panter, I, and Walton Rogers, P, 2015, ‘Pewter funerary chalices and patens from York Minster’, Medieval Archaeology 59, 193-210.

Pewter chalices and patens were recovered from 25 graves during the 1966-73 excavations at York Minster. They were probably made for burial rather than intended for use in the eucharist – as witness the relatively high lead content of several of the chalices (lead was already known to be toxic). Pewter chalices followed the design of 13th-century silver chalices for at least 300 years and are therefore difficult to date, though some of the York Minster examples could be dated by context, some to the 13th century and others to later phases. The patens were either dished with a rim, or flat, the latter sometimes being incised with six-petal flowers: the two types were used concurrently in the 13th to 16th century. Traces of medium-fine textiles preserved in association with four chalice-and-paten sets have been identified with the ‘fair linen’ used in the eucharist.

Walton Rogers, P, 2015, ‘Textiles’ in A Hicks, Medieval Town and Augustinian Friary: Settlement c 1325–1700 (Canterbury Whitefriars Excavations 1999–2004), The Archaeology of Canterbury 7, 266-70. Canterbury Archaeological Trust: Canterbury.

Nearly 300 fragments, representing approximately 40 fabrics were recovered from the Whitefriars excavation. The stratigraphic dates indicated that the earliest were Anglo-Norman and the latest 17th-century, but the greatest number came from the final phase of the friary’s use, in the 16th century. They represented the standard range of clothing and household textiles of the medieval and post-medieval periods, except for one poorly preserved patterned piece, which was tentatively identified as linen damask, and possibly an import. The presence of chalk and oyster shells in the friary cess tank and latrine room allowed the survival of an unusual number of linens. In some instances, flax and hemp could be distinguished with the help of a polarising microscope. The mechanism whereby they are likely to have been preserved was reviewed.

2014

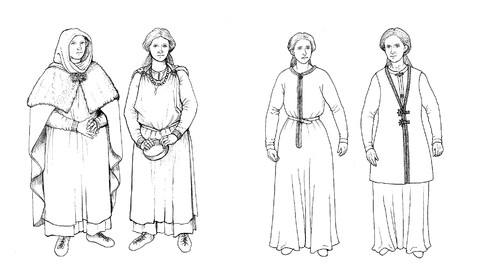

Walton Rogers, P, 2014, ‘Cloth, clothing and Anglo-Saxon women’, in S Bergerbrant and S H Fossøy (eds), A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen (Gotarc series A. Gothenburg Archaeological Studies 4), 253-80. Gothenburg (Sweden): University, Department of Historical Studies.

A review of archaeological and historical evidence from England in the 5th to 11th centuries AD. The aim of the paper was to show how concentrating on women, and those aspects of their lives revealed through their textile crafts and clothing styles, can offer an alternative perspective on Anglo-Saxon society.

Walton Rogers, P, 2014, ‘Textile production and treatment’ pp285-94 (incorporating a contribution, p293, on glass slickstones/linen-smoothers by V Evison), in A Tester, S Anderson, I Riddler and R Carr, Staunch Meadow, Brandon, Suffolk: A High Status Middle Saxon Settlement on the Fen Edge East Anglian Archaeology 151. Bury St Edmunds: Suffolk County Council.

Evidence for a full range of textile crafts, including fibre preparation, dyeing, spinning, weaving, needlework and laundry, was recovered from Middle Anglo-Saxon levels. Production appears to have been relatively small-scale, but appropriate to the needs of the settlement. The range of types, sizes and weights of the equipment was typical of agrarian sites, but incorporated some features indicative of high-status and/or specialist production. These were madder-stained potsherds, a greater number of lightweight spindle whorls and loom-weights than at other contemporary sites (apart from Flixborough), single-ended pin-beaters associated with the two-beam vertical loom and blown-glass slick-stones. Linen production was particularly well represented, as it was at Flixborough, and it was suggested that the emphasis on wool production implied by the quantity, age and sex of the sheep bones (Crabtree pp300-3) might represent fleeces being sent out of the settlement, perhaps to supply places such as Ipswich.

Solazzo, C, Walton Rogers, P, Weber, L, Beaubien, H F, Wilson, J, Collins, M, 2014, 'Species identification by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) in fibre products preserved by association with copper-alloy artefacts', Journal of Archaeological Science 49, 524-535.

Peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) was used to identify the species in mineral-preserved animal-fibre products. Two samples of animal pelts from a Viking-Age grave at Cumwhitton in Cumbria, England, had already been identified by microscopy, one as sealskin and the other, more tentatively, as sheepskin. PMF provided important confirmation for both. Textile samples in different degrees of mineral-preservation from a grave at Gol Mod in Mongolia (300 BC- 200 AD) were also used to test the efficacy of PMF on fibres in different stages of mineralisation. Identification to species (sheep) was possible in all but one sample. The conclusion was that PMF can be a useful tool for identifying species in partially mineralised animal fibres.

Solazzo, C, Wilson, J, Dyer, J M, Clerens, S, Plowman, J E, von Holstein, I, Walton Rogers, P, Peacock, E E, Collins, M J, 2014, ‘Modeling deamidation in sheep α‑keratin peptides and application to archeological wool textiles’, Analytical Chemistry (publication of American Chemical Society), 86, 567-75. dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac4026362

Brettell, R C, Schotsmans, E M J, Walton Rogers, P, Reifarth, N, Redfern, R C, Stern, B, Heron, C P, 2014, ‘‘Choicest unguents’: molecular evidence for the use of resinous plant exudates in late Roman mortuary rites in Britain', Journal of Archaeological Science [--], 1-10.

Organic residues from forty-nine late Roman inhumations from Britain were analysed for biomarkers diagnostic of resinous substances, using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Terpenic compounds were characterised in fourteen of the burials. They provided chemical evidence for the exudates from three different plant sources, coniferous Pinaceae resins, Mediterranean Pistacia resins (mastic/terebinth) and Boswellia gum-resins (frankincense/olibanum) - this last from southern Arabia or beyond. At a practical level, these substances would mask the odour of decay and provide short-term preservation of the body. Most importantly for the archaeologist, however, they were expensive materials which must have been transported over long distances to reach Britain. They proved to be associated with graves which had other attributes of status.

Miller, J, Clydesdale, A, and Walton Rogers, P, 2014, Basketry [from the West Cist at Crantit] pp66-74 in B Ballin Smith, Between tomb and cist: the funerary monuments of Crantit, Kewing and Nether Onston, Orkney. Orkney: The Orcadian (Kirkwall) for Historic Scotland.

A spread of mineral-preserved basketry fragments in one of the Neolithic cists at Crantit.appeared to represent the remains of two separate containers. They were associated with the cremation burials of two adults, one male, one female. The fragments were made of grass or sedge. The best preserved pieces were worked in rhomboidal twining and areas of shaping suggested a flagon- or flask-like vessel. The material was reviewed in the context of other European finds of Stone Age and Bronze Age basketry.

Walton Rogers, P, 2014, ‘Coir cordage’, p94 in L Fowler and A Mackinder, Medieval Haywharf to 20th-century Brewery: Excavations at Watermark Place, City of London, MOLA Archaeology Studies Series 30. London: MOLA.

Three lengths of coir cordage were recovered from the late 13th-century river frontage. This is unusually early for coir (coconut fibre), although there are two other late medieval examples from Bergen and Oslo. They are likely to have arrived as packaging-string around goods imported from tropical countries.

Four cloth seals are described by the main authors on p78; a ball of wool yarn, and textiles, including a 13th-century silk fingerloop braid, by Frances Pritchard on pp82-3; and a hair-moss plait by Allan Hall on pp93-4.

2013

Walton Rogers, P, 2013, Tyttel’s Halh: The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Tittleshall, Norfolk, East Anglian Archaeology 150.

Tittleshall stands to the west of the Launditch earthwork, on a long-term north-south boundary, in west-central Norfolk. A small Anglo-Saxon burial plot was excavated there by Network Archaeology, to the south of the modern village. The 28 individuals identified in the inhumations and cremation burials include men, women and children interred over the period from the 5th to the 7th century. These have been interpreted as the dead from a single farmstead (probably located immediately to the east of the cemetery). Three children’s burials are of particular interest, their clothing reconstructed in line-drawings. A theory has been tentatively advanced that the inhumations represent the core lineage and the cremations other members of the household. The report includes Correspondence Analysis of women's burials on the Wensum-Yare-Waveney river system; a review of place-names in relation to local landholding patterns; and fresh evidence for the north-south boundary, to add to the material published in 2012, ‘Continuity within change’ (below).

http://www.oxbowbooks.com/oxbow/tyttel-s-halh-the-anglo-saxon-cemetery-at-tittleshall-norfolk.html

Walton Rogers, 2013, ‘Textiles’, pp197-8 in B M Ford, D Poore, R Shaffrey and D R P Wilkinson, Under the Oracle. Excavations at the Oracle Shopping Centre Site 1996-8: the Medieval and Post-Medieval Urban Development of the Kennet Floodplain in Reading. Thames Valley Landscapes Monograph 36. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology.

Offcuts from the re-working of wool clothing were found in medieval layers and were dated on stratigraphy and textile technique to the later 14th century. There were four different fabric-types, variously dyed, and the range of fleece-types suggested a variety of sources for the wool. The historical evidence for the Reading wool trade and cloth industry was briefly reviewed. Fragments of coarse knitting, possibly from a stocking came from 16th-century levels and, from a 17th-century deposit, an unusually well preserved length of plant-fibre sackcloth with a complete loom width of 260 mm. Finally, from the period 1680-1750 there were fragments of fulled wool cloth and a blue-dyed wool diagonal plait, possibly finger-looped.

Becket, A, and Batey, C E, with contributions from P R J Duffy, J Miller and P Walton Rogers, 2013, ‘A stranger in the dunes? Rescue excavation of a Viking Age burial at Cnoc nan Gall, Colonsay’ Prcoeedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 143, 303-18.

The body of a middle-aged male was found in a grave dated to the mid-late 10th century AD. The man had been buried with a Hiberno-Norse ringed pin, a copper-alloy strap-end and a knife associated with a bone implement . On the back of the body, where it had probably been fastened by the ring-headed pin, was a medium-coarse linen textile that appeared to have seen heavy usage (p312): this was interpreted as a wrapper for the body. Elements that could have come from a birch-bark bier or coffin were also recovered.

2012

Walton Rogers, P, 2012, ‘Continuity within change. Two sites in the borders of the former Iceni territory in East Anglia’, pp109-121 in R.Annaert, T.Jacobs, I.In't Ven, S.Coppens (eds), The Very Beginning of Europe? Cultural and Social Dimensions of Early-Medieval Migration and Colonisation (5th-8th century) (Papers from the ACE Conference, Brussels May 17-19 2011), Relicta Monografie 7. Brussels: Flanders Heritage Agency.

This paper presents evidence that part of northern East Anglia retained a local identity within the broader ‘Anglian’ culture of eastern England in the 5th and 6th centuries. It is argued that this area represents the contracted remains of the tribal territory of the Iceni and the civitas Icenorum of the Roman period. The recognition of this residual territory has helped in the interpretation of two sites on its borders, Tittleshall (Norfolk) and Flixton (Suffolk). The changing character of the two sites over the 5th to 7th centuries is summarised.

Boulter, S, and Walton Rogers, P, 2012, Circles and Cemeteries. Excavations at Flixton Park Quarry Volume 1. (East Anglian Archaeology 147).

The excavations on the south side of the Waveney Valley at Flixton, Suffolk, uncovered a Neolithic post-hole circle and a series of ring-ditches representing Bronze Age barrows. The Iron Age/Roman archaeology included an enigmatic palisaded enclosure made up of closely-spaced posts describing a near-perfect circle. Anglo-Saxon occupation was deliberately planted in this landscape: the settlement was constructed on a ridge close to the river, where it incorporated the largest barrow, while two cemeteries were arranged so that both would have a barrow as a backdrop when viewed from the settlement. The settlement is to be published in Volume 2, but the two cemeteries appear as part III of Volume 1. Only one grave was excavated at Flixton cemetery I, although metal-detected finds suggested other graves nearby. Flixton cemetery II was at first contained within a rectangular plot, where 51 of an estimated 200 or more graves were excavated. Burial later shifted southwards to the barrow itself, where eleven more graves were identified. The excavated graves in Flixton II date from the end of the 5th to the middle of the 7th century, and Flixton I is likely to have been contemporary with its earliest phase. The material evidence has been used as a base from which to discuss the social make-up of the community who placed their dead in the two burial grounds. The role of this community in the southern marches of the former Iceni territory has also been explored.

http://www.oxbowbooks.com/oxbow/excavations-at-flixton-park-quarry-volume-1.html

Walton Rogers, P, 2012, ‘Textiles, pelts and related organic finds’, pp197-217 in G Sveinbjarnardóttir, Reykholt: Archaeological Investigations at a High Status Farm in Western Iceland, Publications of the National Museum of Iceland, 29. Reykjavik: Snorrastofa and the National Museum of Iceland.

Excavations at Reykholt, famous as the farm of the 13th-century writer, Snorri Sturluson, have revealed an occupation sequence stretching from the 11th to the 19th century. Thirty-one textiles from the excavation have been dated to phases 1-3, the 11th to 16th centuries, 98 textiles to Phase 4, the 16th and 17th centuries, and 71 to Phase 5, the 17th to early 19th century. The textiles show a remarkable degree of correlation with Icelandic written sources. The reliance on plain wadmal twills in the early phases, the rise of heavy fulling, the use of plied yarns and the arrival of knitting, are all features recorded in contemporary documents. Other probably Icelandic products include wool tablet-woven bands with simple patterns, and a single fragment of patterned knitting. Imported wool textiles with a nap first appear in late Phase 3, felts in Phase 4, and a textile made of wild silk early in Phase 5. Further items of interest include two balls of wool yarn, which appear to have been used for rubbing or polishing; raw wool and spinners’ waste; and animal pelts including sheepskin. The stable isotope composition in the wool, wool textiles and sheep bones has been investigated in a study to be published separately by Isabella von Holstein.

Walton Rogers, P, 2012, ‘Costume and textiles’, pp179-235 in K Parfitt and T Anderson, Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, Dover Excavations 1994, The Archaeology of Canterbury New Series Volume VI. Canterbury: Canterbury Archaeological Trust

Out of the 244 graves in this cemetery, 151 bodies were buried with costume accessories and/or textiles. The evidence had a bias towards the burials of adult females, although useful evidence was also acquired for the graves of adult males and juveniles. Using the protocol described in Walton Rogers 2007, Cloth and Clothing, the arrangement of costume accessories in the graves was reviewed and dress styles identified. The textile evidence, including tablet weaves, gold thread and button loops, was then appended, and other organic materials, including cords, feathers and animal pelts, were incorporated. Using evidence from a range of sites, the development of East Kent women’s costume was presented as a sequence of Dress Styles. The implications, including the evidence for the short-term adoption of Frankish fashions, are discussed. Noteworthy features include the function of iron coil-headed pins (not garment-fasteners); a string of brooches tied together by a cord and placed on the body; developments in necklace fashions; the function of tabby repps recovered from the waist area; 2/1 twills; fine ZS diamond twills with a 20 x 18 pattern repeat; and vertical tablet bands which may represent the border of a warrior jacket, from two men’s graves.

http://www.oxbowbooks.com/oxbow/buckland-anglo-saxon-cemetery-dover.html

Author’s correction. On reflection, Fig.5.1, p179, probably would have benefited from a more detailed caption, as follows ‘Fig.5.1. Buckland 1994. The costume evidence for the different age and sex/gender groups shows a bias towards female burials with garment accessories. From left to right, the pie-graphs represent (i) 120 bodies buried with garment fasteners such as pins, brooches and buckles; (ii) 16 bodies with no garment fasteners but decorative accessories such as necklaces and rings.; (iii) 15 bodies with no garment fasteners or decorative accessories, but textiles adhering to other metalwork in the grave; (iv) 93 graves with no relevant grave goods or textiles.

Walton Rogers, P, 2012, 'Fibres and textiles' in R Cowie, L Blackmore, L Davis, J Keily, Lundenwic: Excavations in Middle Saxon London 1987-2000 (MoLA Monograph 63), 302. London: Museum of London.

A small contribution to a major publication. The brief note on p302 is concerned with the imprint of two textiles in some daub from site H (45-47 Floral Street and 51-54 Long Acre). The whole book is worth reading, however, if you are interested in Middle Anglo-Saxon London. It contains a survey of the evidence from 18 sites excavated in the wic and includes a comprehensive review of the regional and international context. For those with an interest in textiles, the finding of a denticulated blade, almost certainly from a toothed weft-beater, from late 7th- to mid 8th-century Site P (Bruce House, 1 Kemble Street), with parallels at another unpublished site, is particularly exciting (pp156-7, 273), as it suggests that the elusive two-beam vertical loom was in use in Lundenwic.

Karsten, A, Graham, K, Jones, J, Mould, Q, and Walton Rogers, P, 2012, Waterlogged Organic Artefacts. Guidelines on their Recovery, Analysis and Conservation. London: English Heritage.

Part of the English Heritage Guidelines series, this aims to help excavators and finds officers who have to deal with artefacts made of organic materials, including fibre products of different sorts. Well illustrated, with numerous case studies.

The whole document is available as a free download at Organic Artefacts.

Walton Rogers, P, 2012, 'Textile remains and skin products’ in S J Sherlock, A Royal Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Street House, Loftus, North-East Yorkshire (Tees Archaeology Monograph Series 6), 70-2.

This 7th-century cemetery was located within an Iron Age enclosure on a headland north of Staithes. It had a formal layout, two contemporary buildings, a possible shrine and a central bed burial. It has been interpreted as a conversion period cemetery associated with a local aristocracy within the kingdom of Northumbria. No human remains were preserved and organic survival was poor, but it was clear that several of the bodies had been buried fully clothed, rather than in shrouds. The mineral-preserved remains on twelve objects from ten graves included a spin-patterned tabby-weave and two ZS 2/2 diamond twills. Remains of a sheepskin, a skin bag for a chatelaine and four seamed knife sheaths were recorded.

2011

Walton Rogers, P, 2011, with a contribution from I.von Holstein, ‘Textiles and clothing’, pp116-125 in A.Pearson, B Jeffs, A Witkin, H MacQuarrie, Infernal Traffic: Excavation of a Liberated African Graveyard in Rupert’s Valley, St Helena. CBA Research Report 169.

The graveyard belongs to a period in the mid 19th century when the British navy was trying to wipe out the transatlantic slave trade. Many of the 325 skeletons are likely to represent Africans rescued from slave ships and brought ashore at St Helena. Textiles were preserved in only 23 graves (25 individuals). Loosely woven striped fabrics, all alike, with stripes dyed with Prussian Blue, were tentatively identified as a form of sackcloth, which had been re-used for head coverings and garments wrapped around the hips: these were compared with 19th-century West African clothing. Remains of buttoned cotton trousers and three tweed-like fabrics are more likely to represent European clothing. Four stillborn or newborn babies had been buried with special care, in coffins with the kinds of textile furnishings found in Britain in the graves of the well-to-do. They included satin ribbons, wool unions, cotton tabby and a silk gauze. One of the coffins contained a pillow, stuffed with the cut-up remains of a worsted twill garment, the subject of a study by Isabella von Holstein.

Walton Rogers, P, 2011, ‘Textiles’, in K. Penn, The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Shrubland Hall Quarry, Coddenham, Suffolk, East Anglian Archaeology 139, 81-3. Bury St Edmunds: EAA and Suffolk CC.

There were 50 burials at this site, but few included grave goods and textile preservation was limited to eleven graves, all dated to the later 7th century. Five were male-gender, three possible male-gender and three female-gender. Women’s clothing was poorly represented, but of interest in the male graves were a fine linen tabby repp at the waist in one; and a medium-coarse tabby of unbleached plant fibre, hemp or low-grade flax, with a thick wool ZS diamond twill made of pigmented wool in another. There was also evidence for soft-furnishings, in the form of a possible coverlet and a piled rug; wrappers for objects, including a fringed cloth with remains of needlework; and yarns/cords for stringing beads and binding metalwork. The bed in grave 30 incorporated a coarse wool twill in the construction, possibly as a support layer pinned to the frame, between the cord suspension and the mattress, with a fine twill on the foot- and headboards.

Walton Rogers, P, 2011, ‘Textiles and other miscellaneous items from BWH97 and BWH98’, pp105-6 in J Lee, Excavations at Blanket Row, Hull, 1997-2003, East Riding Archaeologist 13. Hull: East Riding Archaeological Society.

Remains of four poorly preserved tablet-woven bands in association with metal fittings, three of linen and one of wool; leather thongs inside metal aglets; a caulking roll of cattle hair; and a textile imprint in brick - all from late medieval and post-medieval levels

Walton Rogers, P, 2011, 'Textiles', pp220-1 in R Brown and A Hardy, Trade and Prosperity, War and Poverty: an Archaeological and Historical Investigation into Southampton's French Quarter, Oxford Archaeology Monograph 15. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology.

A relatively coarse wool 2/1 twill from an Anglo-Norman cess-pit, a charred linen tabby from a 14th- or 15th-century demolition layer and a heavy wool tabby from late 15th- to early 16th-century deposits are all typical of urban textiles of the periods from which they come. They contrast with the textiles and palm-fibre cordage from Cuckoo Lane, published in 1975 by Elisabeth Crowfoot, which were imports from the Mediterranean world.

Walton Rogers, P, 2011, four separate entries in Part 2 of W Rodwell and C Atkins, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire: A Parish Church and its Community Vol 1: History, Archaeology and Architecture (published in two parts). Oxford: Oxbow.

'Silk and gold textiles from Grave F325’ incorporating EDXRF analyses by Phil Clogg, Durham University, pp634-8.

The archaeological evidence placed Grave F325 in the mid-to-late 14th century. The burial was that of a young woman – in itself unusual for an intra-mural burial. On top of the coffin, there were remains of a textile complex, mostly preserved as casts in re-deposited mortar, with a residue of threads and fibres in some of the imprints. Painstaking investigation allowed the find to be reconstructed as a ‘cloth-of-gold velvet’ that had been backed with linen, embroidered, and trimmed with gold-brocaded tablet-woven bands. The gold thread used in the brocade proved to be metal-on-gut strip, spun around a linen core, a type that was made in late medieval Italian and German workshops. The gold threads of the embroidery and the brocaded bands, on the other hand, were made from foils of silver-gold alloy (not silver-gilt), spun around a silk core. These could have been made in private or monastic workshops anywhere in Europe. It was not clear whether this was an elaborate funeral pall, or a smaller item such as a hat, placed on top of the coffin.

'Internal textile from Grave F425’, p638-9.

Simple linen tabby, possibly the remains of a winding sheet, were recorded in the burial of a man.

'Coffin covers’, p701-3.

Remains of fitted coffin covers were recovered from the 18th- and 19th-century (up to AD 1855) graves. The covers were made of black wool baize-like fabrics, all of which had a similar napped appearance, though analysis revealed that they had been made from fine wool worked in different weaves, with different dyes used to achieve the black colour. There was also a single example of a fine worsted twill, interpreted as the remains of an upholstery tape used to trim the coffin. One associated textile was a wool-cotton union, which may have been from a coffin lining rather than a cover. Ribbons were identified on the coffin grips (handles).

'Internal textiles and fibres from burials’ p711-13

A typical range of coffin linings and winding sheets were recovered, along with fragments of wool flannel shrouds. Interesting details included cotton-bound cartwheel buttons and the remains of a silk bonnet with a wire frame. This last will have been worn in life, while the other textiles will have been made specifically for the funerary trade.

2010

Walton Rogers, P, 2010, ‘Textiles and leather’ in Booth, P, Simmonds, A, Boyle, A, Clough, S, Cool HEM and Poore, D, The Late Roman Cemetery at Lankhills, Winchester: Excavations 2000-2005 (Oxford Archaeology Monograph 10), 309-311. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology.

Remains of textiles and leather were recorded in nine 4th-century graves. They included two textile-types typical of the Roman period, basket weave and half-basket weave (extended tabby). Most of the textiles probably represent household linens used to shroud the body, but the woman in Grave 780 appears to have been buried in a wool garment clasped by a brooch, with hobnail sandals on her feet. Comparable clothed late Roman burials are reviewed.

Also of interest to textile researchers is a report by Hilary Cool (pp274-6) on six turned shale spindle whorls and one bone one. The significance of an increase in the frequency of spinning equipment in late 4th-century graves is discussed.

Walton Rogers, P, 'Textiles and fibre on the Noak Hill Late Iron Age mirror handle', pp98-9, in M Medlycott, S Weller and P Benians, 'Roman Billericay: excavations by the Billericay Archaeological and Historical Society 1970-77', Essex Society for Archaeology and History 1, 51-108

Unburnt organic remains were preserved on a copper-alloy mirror handle. The handle was dated to the Iron Age, but came from a Roman cremation cemetery, burial N19, at Noak Hill Road, Billericay. The burial was that of a young adult, probably female to judge from the brooches, and a young child. The organic remains included a medium-coarse matted textile, probably of wool; finer threads, probably from a fringe; and an animal pelt of unknown species.

2009

Dawkes, G, Goodburn, D, and Walton Rogers, P, 2009, ‘Lightening the load: five 19th-century river lighters at Erith on the River Thames, UK’, International J. of Nautical Archaeology, 38/1, 71-89

Five early 19th-century Thames lighters were excavated at Erith, on the south bank of the Thames estuary, where they had been re-used in a river wall. They are examples of a distinctive local craft, broad, blunt-ended, flat-bottomed and built ‘bottom first’ (as distinct from carvel- and clinker-built). They will have been used to carry goods from larger ships, or for local transport, and, being without sails, will have been manoeuvred on the tide or pulled in rows by steam-tugs. Samples of the caulking materials proved to be goat hair, cattle hair and in one instance shredded jute, waterproofed with both wood and coal tars (the layering suggested repeated repairs). Cordage from one of the vessels was made of coir (coconut fibre).

Walton Rogers, P, 2009, ‘Textile production’, pp281-316 in D H Evans and C Loveluck, Life and Economy at Early Medieval Flixborough c.AD 600-1000: The Artefact Evidence (Excavations at Flixborough 2).Oxford/Oakville: Oxbow.

Over 1,100 items related to the production of textiles were recovered from levels dated to the mid 8th to 11th centuries. They represent a full sequence of textile crafts, from flax processing and wool combing, through spindle-spinning and warp-weighted loom-weaving, to the cutting and stitching of garments. The presence of particularly small spindle whorls, loomweights, pin-beaters and needles in Phase 4 was taken to indicate specialist manufacture in the first half of the 9th century. Features of interest include lathe-turned spindle whorls and loomweights with impressed marks. The warp-weighted loom evidently remained in use in the 10th century, when most urban centres had switched to the two-beam vertical loom. The significance of these findings is reviewed in a different volume: see Walton Rogers 2007 [Flixborough], below.

Lucy, S, Newman, R, Dodwell, N, Hills, C, Dekker, M, O’Connell, T, Riddler, I, Walton Rogers, P, 2009, 'Burial of a princess? The Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Westfield Farm, Ely', The Antiquaries Journal, 89, pp81-141.

A small, high-status cemetery dated to the later 7th century at Westfield, Ely, included at least 15 graves. The grave of a juvenile buried with necklace of pendants and other signs of status appeared to be the focus of the burials and another burial, that of teenager, was also well furnished with female-gender accessories. The textiles in the graves were poorly preserved, but folds of fabric and different weights of cloth could be recognized in four graves and the position of costume accessories in others implied that some, if not all, bodies had been buried fully clothed. The presence of a fine tinder pouch thought to be made of parchment, in association with a firesteel in the central grave, was also of interest. It was argued that the cemetery may have been associated with the first monastery in Ely, founded by Etheldreda in AD 673.

Walton Rogers, P, 2009, 'Woolcombs', pp393 & 409-10, and 'Textiles', pp411-4, in S Lucy, J Tipper and A Dickens, The Anglo-Saxon Settlement and Cemetery at Bloodmoor Hill, Carlton Colville, Suffolk, East Anglian Archaeology 131. Cambridge: Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

A pair of woolcombs was buried below the feet of a body with female-gender accessories, in a well-furnished 7th-century burial. They represent an early example of the short-toothed, flat-headed two-row type, which continued in use in England until the 13th or 14th century. The mineral-preserved textiles recovered from five graves were mostly of standard types, but interesting features included a fine, probably hempen, tabby weave with a Roman-style corded selvedge; a coarse wool 2/2 ZS twill with a wide tabby-woven border; and a linen-and-wool textile which might represent fine tapestrywork.

These finds were recovered from two areas of 7th-century burial (reported by C Scull on pp384-426) within the 6th- to 8th-century settlement.

Vanhoutte, S, Bastiaens, J, De Clerq, W, Deforce, K, Ervynck, A, Fret, M, Haneca, K, Lentacker, A, Stiepaere, H, Van Neer, W, Cosyns, P, Degryse, P, Dhaeze, W, Dijkmanm, W, Lyne, M, Walton Rogers, P, van Driel-Murray, C, van Heesch, J, Wild, J P, 2009, 'De dubbele waterput uit het laat-Romeinse castellum van Oudenburg (prov. West Vlaanderen): tafonomie, chronologie en interpratatie', Relicta 5, 9-142. Brussels: Vlaams Instituut voor het Onroerend Erfgoed.

The Roman fort at Oudenburg, West Flanders, in the latest phase of its use, was probably part of the Saxon Shore defence system. This report is concerned with a double well in the south-west corner of the fort itself. The outer shell was constructed in the later 3rd century, then an inner framework was inserted in the last quarter of the 4th century, and the well was abandoned at the beginning of the 5th century. The good preservation of organic remains meant that the local ecology could be reconstructed. Dumped waste included pottery, animal bones, leather shoes for men, women and children, including a decorated mule-like slipper (text pp100-1, illustrated p78), and wool textile fragments. Two textile types were identified (text pp101-2, illustrated pp54 & 68), one plain and the other a 2/2 chevron twill with paired warp and a raised pile on one face.

Walton Rogers, P, 2009, 'Textiles', p54 in N Emery and J Langston, 'Excavations at the church of St Mary-the-Less, Durham City', Durham Archaeological Journal 18, 39-65.

The textiles recovered from a small group of 18th-century coffins were considered in relation to the status of the dead. In the Bowes vault, silk velvet was used to cover the coffin of Dame Elizabeth Bowes - which would have required a fine to be paid to the crown - but wool baize covered the coffins of her unmarried daughters. One coffin had been lined with a napped wool tabby and two had upholsterer's tape at the join between inner and outer covers. The remains of a bonnet made of silk open-weave textile, netting and tape, mounted on wire, from a (possibly later) burial in the nave are of interest.

Walton Rogers, P, and Hall, A R, 2009. ‘Appendix 2: Caulking materials used in The Mary Rose’, pp404-7 in P Marsden and P Crossman, The Mary Rose: Your Noblest Shippe: Anatomy of a Tudor Warship (Archaeology of The Mary Rose 2).

2008

Walton Rogers, P, 2008, 'Textiles', pp305-6 in P Booth, A-M Bingham and S Lawrence, A Roadside Settlement at Westhawk Farm, Ashford, Kent, Excavations 1998-9 (Oxford Archaeology Monograph 2). Oxford: Oxford Archaeological Unit.

A strip of folded tabby-weave linen appears to have been wrapped around the broken handle of a copper-alloy patera recovered from a Late Iron Age cremation burial. The fibre was well preserved and identified as fully processed flax, from Linum usitatissimum L. The find was related to comparable material from other sites.

2007

Walton Rogers, P, 2007, Cloth and Clothing in Early Anglo-Saxon England (AD 450-700) (CBA Research Report 145). York: CBA.

This volume draws on a range of archaeological, historical and art-historical evidence to reconstruct the clothing of the Early Anglo-Saxons. It describes the tools, raw materials and processes of manufacture and explains how women were the directors of the craft. It summarises the technical features of 3,800 textiles recovered from 162 cemeteries and places them within their national and European context. One chapter is dedicated to the, mostly metal, brooches, pins and buckles used to fasten the garments. This is followed by a detailed review of costume styles, including belts, necklaces, bags and shoes. By means of a new protocol for the interpretation of costume in clothed burials, the research uncovers regional, social and gender differences in clothing and accessories.

Walton Rogers, P, 2007, ‘Textile remains’, p26 and plates 3-4 on p6, in P R Sealey, A Late Iron Age Warrior Burial from Kelvedon, Essex, East Anglian Archaeology 118. Colchester: Colchester Museums (Colchester Borough Council).

Folds of a linen tabby textile were preserved on one face of an iron sword blade. The sword came from a poorly documented excavation of a 'warrior burial', dated on the artefacts to c 75-25 BC, though whether it had been an inhumation or a cremation could not be determined. The comparative material for Iron Age linens was reviewed.

Walton, P, 2007, ‘Fragments of textile’, p151 I Soden (ed) Stafford Castle, Survey, Excavation and Research 1978-98, Vol.2, The Excavations. Stafford: Stafford Borough Council.

Two fragments of silk were recovered from a 16th-century well pit. One was woven in 8-end satin and the other in 5-end satin, brocaded with silver thread in a small diamond pattern. The latter was made up of three pieces stitched together. [The weave diagrams were omitted: we plan to publish them with other unpublished material from Civil War castles in due course.]

Walton Rogers, P, 2007, ‘The importance and organisation of textile production’, pp106-111 in C Loveluck, Rural Settlement Lifestyles and Social Change in the first Millennium AD: Anglo-Saxon Flixborough in its Wider Context (Excavations at Flixborough 4). Oxford: Oxbow.

The site at Flixborough, Lincolnshire, has been interpreted as a rural estate centre, occupied by a secular elite in the 8th century, possibly transformed into a monastic holding in the early 9th century, but secularised again in the later 9th century. The evidence of the textile tools reported in volume 2 (Walton Rogers 2009, above) indicates the production of fine fabrics and garments in Phase 4. Despite the extensive evidence for the female cloth-working crafts, there is no material evidence for tablet-weaving or any particular emphasis on needlework, as might be expected if this were a nunnery. Written sources and archaeological evidence have been combined to argue that the purpose of the textile tools was to produce good quality cloth to support the owners of the estate, but any surplus could have been taken away by merchants. By the 10th century there had been a shift to the production of coarser cloths and probably also a greater emphasis on wool: by this time, the production of the finer qualities of cloth may have shifted into towns.

Walton Rogers, P, 2007, ‘Textiles’, pp232-5 in J Nolan and J Vaughan, ‘Excavations at Oakwellgate, Gateshead, 1999’, Archaeologia Aeliana 5th series, 36, 125-249.

Twenty-five textile fragments from 17th-century deposits proved to include two coarse woollen tabbies, one made of naturally brown wool; a heavily worn and re-used worsted satin, possibly an example of the fabric known as ‘russell'; remains of a goat-hair garment, probably a coat or jacket, with a second example possibly also goat-fibre; together with medium and coarse linens. The textiles were compared with other urban collections of the period and it was suggested that they would fit most naturally the clothing of artisans and agricultural workers.

Other organic objects reported from this site included a basket woven from sedge, a wooden bowl, a hollow wooden object, possibly a rattle, a welted shoe with a stacked heel and a pair of randed shoes with a slashed vamp.

2006

Walton Rogers, P, 2006, ‘Textiles’ in M Brickley, S Buteux, J Adams, R Cherrington, St Martin’s Uncovered: Investigations in the Churchyard of St Martin’s-in-the-Bull Ring, Birmingham, 2001, 163-178 (with seven colour plates between pp190 and 191). Oxford: Oxbow.

Textiles were recovered from 117 of the 857 burials in this 18th- and 19th-century churchyard. They included black wool baize coffin covers; undyed wool cloths, and wool unions, used for linings and winding sheets; wool shrouds, face cloths (one with a pinked and punched decoration), pillows and their trimmings; wool treated to give it a linen-like appearance; a child’s mattress with pinked rosettes; and a variety of silk ribbons, bows and covered buttons. Most of these would have come from the undertaker’s stock, but there were also remains of a dress in an elderly woman’s grave, and heavily darned knitted stockings on the legs of a man from a well-to-do family. Subjects covered include the social differences in burial textiles; the regional nature of some of the fabrics; and the unusually late use of wool shrouds and baize coffin covers.

Walton Rogers, P, 2006, [contribution on fibres and dyes] pp80-81 in S Metcalf, A R E North and D Balfour, 'The conservation of a gun-shield from the arsenal of Henry VIII', R Douglas Smith (ed), Make All Sure: The Conservation and Restoration of Arms and Armour, 76-90. .Leeds: Basiliscoe.

A 16th-century, dome-shaped gun-shield from the V&A collection is described. Made of iron-plated wood, with a central boss through which a matchlock pistol would be fired, the shield is lined with a red wool textile, there is a yellow textile to support the arm of the user and an inner lining padded with raw fibre. The red dye proved to be madder, but the yellow had its closest correspondence with curcumin, derived from the Indian dye turmeric. Turmeric is known to have been used in the Italian cloth industry. The liner proved to be made of hemp and the stuffing was either flax or hemp fibre. The historical context of the gun-shield, the textiles and the dyes is discussed.

2005

Walton Rogers, P, 2005, ‘The textiles from Mounds 5, 7, 14 and 17’ pp262-8, in Carver, MOH, Sutton Hoo: A Seventh-Century Princely Burial Ground and its Context. London: British Museum.

Textiles from four of the mounds excavated in Martin Carver’s campaigns included fine textiles comparable with those found in the Mound 1 ship burial. There were remains of a linen tabby-weave seamed garment, perhaps a shirt/undertunic, and examples of tabby repp, 2/1 twill and wool diamond twill. The most significant finds came from the disturbed inhumation of a woman in Mound 14. These were reconstructed as the cuffs of two different sleeved garments, one cuff made up of three parallel bands of tablet weaving and the other embroidered. One of the tablet weaves used a developed form of a Scandinavian technique, in a manner that presaged the tablet bands of later Anglo-Saxon church vestments. The embroidery has been placed in the context of other early medieval embroideries from NW Europe. For a reconstruction drawing of the sleeves, see Walton Rogers 2007, Cloth and Clothing fig.5.41, p185.

Walton Rogers, P, 2005, ‘Gold thread’ pp68-9 and ‘Textile remains’ pp70-1 in V Birbeck, The Origins of Mid-Saxon Southampton: Excavations at the Friends Provident St Mary’s Stadium 1998–2000, 68-9. Salisbury: Wessex Archaeology.

Gold thread wrapped around what was probably once a small bobbin was recovered from an 8th- (or 9th-) century cess-pit on the edge of Hamwic, the trading centre that preceded Southampton. The use of gold thread in Anglo-Saxon embroideries and brocaded bands was reviewed. Other textile remains were recovered from six graves dated to the second half of the 7th or early 8th century at the same site. These were typical of the period, with six ZZ tabby-weaves (one a repp) and two ZS 2/2 twills (one a diamond twill). They represent clothing and textile wrappers from the final phase of clothed burial in Anglo-Saxon England.

Walton Rogers, P, 2005, ‘Report on the animal hide’, p164 in A Sheridan, ‘An early historic steatite urn from Orkney: new information on an old find’, Archaeologa Aeliana, 5th series, 34, pp158-167

Cattle hide from an adult beast with a short-haired, light brown coat had been used to wrap a steatite cremation urn, recently radiocarbon-dated to the early-mid 1st millennium AD (Early Historic). The original 18th-century account of the discovery had recorded the hide as deerskin. The cremated bones have been identified by K.McSweeney as adult male.

Østergård, E, and Walton Rogers, P, 2005, ‘Tekstiler, reb og snor’, pp191-204 & 321-8, in J Kock and E Roesdahl (eds), Boringholm – en Østjysk Træborg fra 1300-årene, Højbjerg (Denmark): Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab.

Approximately 100 fragments of textiles and cordage from a 14th-century castle in East Jutland proved to be mostly made of wool. They were woven in tabby and 2/1 twill, with one example of 2/2 twill, and one of felt. Fragments of a garment made from the winter coat of goat include a worked side slit, a close row of button holes (the earliest button holes from Denmark) and binding strips for the neck or arm-hole. One textile represented an example of a wool blend, identified from the differently dyed fibres. Cords were made from white wool, animal hair and bast.

Walton Rogers, 2005, P, ‘The waterproofing materials in the timber revetments’, pp295-302 in S J Allen, D M Goodburn, J M McComish and P Walton Rogers, ‘Re-used boat planking from a 13th-century revetment in Doncaster, South Yorkshire’, Medieval Archaeology 49, 281-304

Caulking materials were preserved in two medieval revetments constructed from ships’ timbers. They included sausage-shaped fibre rolls, true felts and loose wads of fibre. One revetment was made from timbers dendro-dated to the mid 12th century. The other could not be dendro-dated, although the nature of the caulkage suggested that it was later than the first. The caulkage is discussed in the context of similar material from ports of north-east England and from Bergen, and with medieval documents concerning ship-building.

Correction: the key for figure 7 should read from left to right wool – hair&wool – hair.

2004

Speed, G, and Walton Rogers, P, 2004, ‘A burial of a Viking woman at Adwick-le-Street, South Yorkshire’, Medieval Archaeology 48, 51-90

The grave of a woman wearing 9th-century Scandinavian brooches was excavated in an area of South Yorkshire with no previous evidence for Viking or Anglo-Scandinavian activity. The woman was over 45 years old – possibly much older – and she had suffered from osteoarthritis. She was wearing a non-matching pair of oval brooches, to which adhered remains of a strap-dress over a coarse linen garment. Also in the grave was a copper-alloy bowl, likely to have been of Irish or west-British manufacture, an iron latch-lifter and a knife. The assemblage as a whole found its closest parallels in Norway, where Irish/British bowls were in circulation and were sometimes placed in graves. Shortly before publication, isotope analysis on the tooth enamel (by Paul Budd) demonstrated that the woman had spent most of her childhood in the Trondheim area of Norway. The publication explored the evidence for women in the Scandinavian migration into the British Isles.

Walton Rogers, P, 2004, ‘Fibres and dyes in Norse textiles’, pp79-92 in E Østergård, Woven into the Earth: Textiles from Norse Greenland, Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Over 100 textiles from Greenland, including those used in the garments from the Herjolfsnæs cemetery, were analysed. Most proved to have been made of wool from double-coated vari-coloured sheep. The individual fleeces had been processed, probably with single-row woolcombs, to separate the hairy outer fibre for the warp, from the underwool for the weft. This gives a distinctive profile to the fibre-diameter histograms, which can now be used to identify textiles of Norse origin when they are excavated elsewhere in Europe. Goat hair, Arctic hare fur and flax were also used. A limited number of dyes were identified, traditional Norse/Irish ones in the earliest sites, and then local colorants, including red from iron-rich water, in later ones.

E.Østergård’s book includes many photographs of the Herjolfsnæs costumes and details of their construction. It was previously published (2003) in Danish as Som syet til Jorden: Textilfund fra det Norrøne Grønland.

Walton Rogers, P, 2004, ‘Cordage and caulking’ pp 78-84 in D.Divers, ‘Excavations at Deptford on the site of the East India Company dockyards and the Trinity House almshouses, London’, Post-Medieval Archaeology. 38/1, pp17-132.

A large collection of cordage and caulking materials was recovered from the site of the dockyard founded by the East India Company in the early17th century. The cordage, made of coir (coconut fibre), came from late 18th century deposits, at a time when Dutch-ruled Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was the major supplier. Caulking materials included goat-hair rolls, usually associated with clinker construction, tarred pads of the same fibre, a tarred rabbit-fur felt, a wool textile, and wood tars. The sources of these materials and the role of the caulker in shipyards and on-board ship are discussed.

[Sections of this text appear to have been revised by the editor. Note especially that the fibre of the cordage is coir, not hemp (p78) and that the textile (p83) is a wool tabby, 12/Z x 11/S per cm, unevenly woven and slightly felted.]

Walton Rogers, P, 2004, ‘Die Färbung des äusseren Leichentuches’, pp87-8 in Die Mumie der Ta-di-Isis: Eine Reise vom Nil zum Rhein. Chur (Switzerland): Rätisches Museum.

A pink textile from an Egyptian burial, after an exhaustive investigation, proved to have been dyed with the flowers of safflower, Carthamus tinctorius L. The history of the dye in Egypt was reviewed briefly.

2003

Walton Rogers, P, 2003, ‘The archaeologist and the art collector’, Ghereh: International Carpet and Textile Review 32 (March 2003), pp29-39

The difference between archaeological material and art textiles is described and the ways in which interaction between the two fields can be made more productive. Case studies include the Apsley Arms carpet, an embroidered court dress and Henry VII’s coronation cope. The Textile Research unit’s policy on traded textiles is summarised.

Walton Rogers, P, 2003, ‘Fibres in miscellaneous samples from a site in the Dead Sea region’, pp287-8 in J-B Humbert and J Gunneweg, Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha II (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus Series Archaeologia 3), Fribourg, Academic Press, and Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Walton Rogers, P, 2003, ‘Sewing threads on leatherwork from 16-22 Coppergate and Bedern Foundry’, pp3259-61 in Q Mould, I Carlisle and E Cameron, Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York (The Archaeology of York 17/16). York: CBA for York Archaeological Trust.

Fibres identified by transmitted-light microscopy incorporating polarised light. Evidence presented that there was a slow, and staggered, transition from the predominant use of animal fibres to stitch leather shoes in the Anglo-Scandinavian period to the exclusive use of flax and hemp by the end of the medieval period.

Walton Rogers, P, 2003, 'Remains of textile and animal pelt', pp36-40 in C Johns, 'An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly', Cornish Archaeology 41-2 (2002-3), 1-79.

Mineralised remains of a sheepskin were recorded on the sword hilt. A coarse ZZ textile of uncertain weave, made of fine wool or goat-fibre, was found on a copper-alloy toe- or finger-ring, along with fur from a small mammal. The body was that of a 25-year old, who had been placed on his right side, crouched, with head to the North. Dated to the first half of the 1st century BC.

Walton Rogers, P, 2003, ‘Textiles’, pp91-5 in J I McKinley, ‘The Early Saxon cemetery at Park Lane, Croydon’, Surrey Archaeological Collections, 90, 3-116.

46 inhumations and two cremation burials were excavated by Wessex Archaeology, to add to approximately 104 uncovered in the late 19th century. The full date-range of the site was probably the late 5th to the late 7th century, although the finds were mostly dated to the 6th century. A late Roman or early post-Roman grave was also located. Mineral-preserved textiles were recovered from 14 graves, including a number of male-gender (weaponed) burials. They represented the usual range of wool and linen fabrics woven in ZZ tabby, ZZ 2/2 twill and ZS 2/2 twill. They included coarse pieces, probably wrappers for grave goods, and a fine ZS diamond twill with a 20 x 18 pattern unit, possibly a standardised item of exchange. Other items of interest include a tentatively identified example of ZS 2/1 twill and an animal pelt, both in female-gender graves.

2002

Walton Rogers, P, 2002, ‘Textiles’ in I.Roberts, Pontefract Castle: Archaeological Excavations 1982-86 (Yorkshire Archaeology 8), pub. West Yorkshire Archaeology Service, pp308-314.

Textiles from Civil War (1640s) deposits include dyed wool clothing fabrics and silk textiles. One fragment represents the front opening from a wool doublet and has a re-used piece of silk as the interlining, and close-set button-holes. A lacing made from metal-wrapped thread, and textiles on metal jack plates (armour) are also described.

Walton Rogers, P, 2002, ‘Textile and yarn’, pp2880-2886, and ‘Textile production’, pp2732-2745, in P Ottaway and N Rogers, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Medieval York (The Archaeology of York 17/15), York: CBA.

Two reports, one on the textiles, the other on evidence for textile manufacture, from late medieval sites in York, Bedern Foundry, Bedern Vicars Choral, Aldwark, Fishergate Priory and 22 Piccadilly. Textiles include ‘cloth of ray’, silks, linens and dyed wool cloth; textile manufacture includes waste from a woad vat, knitting needles , netting shuttles, thimbles and so-called ‘couching needles’. Revised stratigraphic dates for medieval material from Coppergate (published 1989 and 1997, see below) are also given.

Walton Rogers, P, 2002, ‘Dye tests on textile fragment from lead coffin’ in S M Davies, P S Bellamy, M J Heaton and P J Woodward, Excavations at Alington Avenue, Fordington, Dorchester, 1984-87 (Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society Monograph Series, 15), pub. Trust for Wessex Archaeology, p159 [and E Crowfoot, ‘Textiles from the lead coffin’, pp158-9].

Dye analysis of textiles from the 3rd-century burial of a juvenile, in a lead coffin, is described. Dibromoindigotin, the chief chemical constituent of shellfish purple, the dye popularly known as ‘Tyrian purple’, was detected in at least two samples. E.Crowfoot’s report suggests that this may have been a male child’s garment, made of undyed wool, with purple clavi and tapestry panels.

Walton Rogers, P, 2002, ‘Caulking materials’ in D Divers, ‘The post-medieval waterfront development at Adlards Wharf, Bermondsey, London’, Medieval Archaeology 36, pp39-117.

Raw animal hair had been stuffed between the boat timbers used for the mid 17th-century revetment at Adlards Wharf. These proved to be predominantly goat hair with some calf hair. [Note that the term ‘luting’ was introduced during editing and is in the author’s view incorrect.]

2001

Walton Rogers, P, 2001, ‘The re-appearance of an old Roman loom in medieval England’, in P Walton Rogers, L Bender Jørgensen and A Rast-Eicher, The Roman Textile Industry and its Influence: a Birthday Tribute to John Peter Wild (Oxford: Oxbow), pp158-171.

The history of the two-beam vertical loom is reviewed. It is argued that this loom survived in northern France in the post-Roman period, came to Britain around AD 900, and is the loom described in Gerefa. It was at first used for 2/1 twill wool clothing fabrics and perhaps the medieval fabric ‘haberget’, until, under competition from the horizontal loom, its use became limited to tapestrywork.

Walton Rogers, 2001, P, ‘Gold thread’ in M Hicks and A Hicks, St Gregory’s Priory, Northgate, Canterbury Excavations 1988-1991, The Archaeology of Canterbury 2: Canterbury Archaeological Trust, pp284-286, and contribution to ‘Iron buckle’, pp286-287.

Extensive gold thread from the neck and lower arms of a priest buried in a coffin at St Gregory’s Priory. The thread was spun gold of relatively high carat. Wool twill and pubic hair were identified on the back of a buckle from a different burial.

Walton Rogers, P, 2001, ‘Tests for dyes’, pp243-4 in M L Ryder, ‘The fibres in textile remains from the Iron Age salt-mines at Hallstatt, Austria’, Anthropologie und Prähistorie, 102A, 223-244.

The blue colorant indigotin, representing woad or indigo, was identified in four greenish-blue yarns, and a red dye which did not correspond with any known standards was detected in one red-brown yarn. No dye was detected in two other yarns. The difficulty of identifying prehistoric red dyes, other than the kermes-red at Hochdorf, was reviewed.

2000

Walton Rogers, P, 2000, ‘Fibre identification and tests for dye’ in K.Penn, Excavations on the Norwich Southern Bypass, 1989-91 Part II: The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Harford Farm, Caistor St Edmund, Norfolk (East Anglian Archaeology 92), pp90-91

It is not usually possible to distinguish flax from hemp in mineral-preserved textiles from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, but in this instance two well-preserved samples from Grave 18 could be identified by microscopy as hemp. The burial is dated to the later 7th century. The full range of textiles is described by Elisabeth Crowfoot on pp82-90.

Walton Rogers, P, 2000, ‘Stone spindle whorls’ in A J Mainman and N S H Rogers, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York (The Archaeology of York 17/14), pp2530-2533.

A large collection of stone spindle whorls were recovered from Anglo-Scandinavian Coppergate. They were immensely variable in shape, size, lithic origin and method of manufacture, although some broad chronological trends could be detected. The raw materials of whorls from a number of different sites is reviewed and their regional nature explored.

1999

Walton Rogers, P, 1999 , ‘The textiles’ in C Haughton and D Powlesland, West Heslerton, The Anglian Cemetery vol. I, The Excavation and Discussion of the Evidence, pp143-171, published West Heslerton, N.Yorks: The Landscape Research Centre.

150 textiles from 97 burials, mostly dated to the 5th and 6th centuries, are described and their likely uses reviewed. The textiles were of wool and linen and were divided into whole cloths woven in tabby and 2/2 twill, including diamond twills and spin-patterned fabrics, and narrow tablet-weaves in a variety of decorative techniques. Some wool textiles are soft-finished. In one woman’s grave there was the upper part of a red headdress, dyed with bedstraw or wild madder, and edged with a tablet-woven border running across the forehead.

Walton Rogers, P, 1999, ‘Textiles’, in P M Stead, ‘Archaeological Investigations at Tavistock Abbey, 1997-1999’, Devon Archaeological Society Proceedings 57, 184-190.

Textiles from two priests’ burials at the Abbey, including remains of gold-brocaded bands and a wool 2/1 diamond twill with a woven starting border.

Walton Rogers, P, 1999, ‘Textile, yarn and fibre from The Biggings’, in B E Crawford and B Ballin Smith, The Biggings, Papa Stour, Shetland: the History and Archaeology of a Royal Norwegian Farm (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph Series No. 15), Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi, 194-202.

A sizeable collection of wool textiles was excavated at the site of a royal Norwegian farm on Papa Stour in The Shetland Isles. It includes a small group of medium-coarse fabrics from the original 12th-century farmstead, together with animal fibre and weavers’/spinners’ waste. Some 200 pieces from less securely dated levels include cloth foot-hose, ‘wadmal’ twills, a grey-and-white check in natural fleece colours and coarse knitted goods. It is argued that many of these textiles were made locally, but that a small number of finer dyed goods came from urban weaving centres.

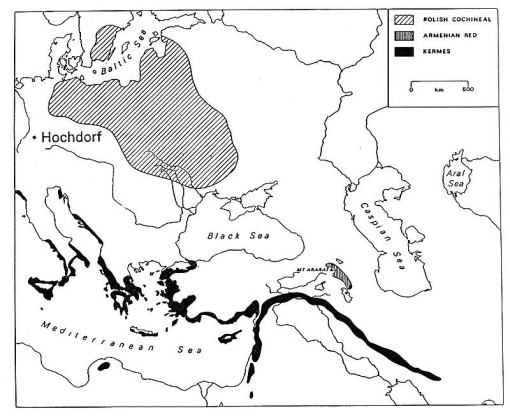

Walton Rogers, P, 1999, ‘Dyes in the Hochdorf textiles’, pp240-5, and ‘Tests for dye in samples from the Iron Age (Hallstatt) site at Hohmichele, Germany’, p246, in J. Banck-Burgess, Hochdorf IV: Die Textilfunde aus dem späthhallstattzeitlichen Fürstengrab von Eberdingen-Hochdorf (Kreis Ludwigsburg) und weitere Grabtextilien aus halstatt- und latènezeitlichen Kulturgruppen, Stuttgart: Kommissionsverlag/Konrad Theiss Verlag.

A detailed account of the identification of kermes and other dyes in the textiles from the late Hallstatt prince’s grave at Hochdorf, Germany. The significance of the Mediterranean insect red dye kermes in Iron Age Germany is discussed.

Walton Rogers, P, 1999, ‘Identification of dye on Middle Saxon pottery from Christ Church College’, Canterbury’s Archaeology 1996-1997 (21st Annual Report of Canterbury Archaeological Trust), p36.

Sherds of a locally made pot dated to the second half of the 8th century were recovered from a rubbish pit at Christ Church College. The pot proved to have madder dye on the inner surface and sooting on the outer, suggesting use as a dyepot.

Walton Rogers, P, 1999, ‘Textile making equipment’ in A MacGregor, A J Mainman and N S H Rogers, Craft, Industry and Everyday Life:Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn from Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York (The Archaeology of York 17/12), pp1964-1971.

Review of the bone and antler weaving tools and ancillary equipment from Anglo-Scandinavian and medieval sites in York. The methods of manufacture and the reasons for the rise and fall of bone tools within the textile industry are discussed.

1998

Walton Rogers, P, 1998 (printed in 2002), ‘Textiles and cordage from Walraversijde (Ostend, West Flanders, Belgium)’, Archeologie in Vlaanderen 6 (for 1997/98), pp303-308.

A small collection of textiles from a 15th-century fishing village in West Flanders included dyed wool clothing fabrics, linen tabbies and two examples of a 3/3 linen diamond twill. Further textiles, cordage and sheepskin from the same site are to be published at a later date.

This report can now be downloaded from the publisher's website AinV

Walton Rogers, P, 1998, ‘The raw materials of the textiles from GUS, with a note on fragments of fleece and animal pelts (identification of animal pelts by H.M. Appleyard), in J. Arneborg and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Man, Culture and Environment in Ancient Greenland, Danish Polar Centre Publication No.4 (published by The Danish National Museum and Danish Polar Centre, Copenhagen), pp66-73.

Analysis of 22 of the textiles excavated at Gården-under-Sandet (GUS), Greenland, confirmed that the Norse had a particular method of preparing wool for spinning and weaving, which produced a coarse-fibred warp and a softer finer weft. Naturally coloured fleeces were often used and the distribution of pigmented fibres indicates that a single fleece was probably separated by combing the wool into warp and weft fibre. Microscopy of surviving fragments of fleece showed they were sometimes ‘rooed’ or plucked from moulting sheep, and sometimes cut or sheared with a knife. A linen or hempen textile, a textile spun from the white fur of the Arctic hare and a black textile with a white stripe of spun fur were also identified. Pelts of animal included goat, cattle, reindeer, (possible) musk ox, black or grizzly bear, Polar bear, bison, wolf and fox. The full range of textiles is described separately by Else E.Østergård, pp58-65.

Walton Rogers, P, 1998, Textiles and Clothing’ in G. Drinkall and M. Foreman, The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Castledyke South, Barton-on-Humber (Sheffield Excavation Reports 6), Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield, 274-279.

Mineral-preserved textiles were recovered from 59 burials, of which 36 were female, 15 male, six youngsters and two indeterminate. They are dated to the 6th and 7th centuries and show a rise in the use of tabby weave over the period, reflecting a greater standardisation in production. Costume details included a vertical tablet-woven band on a man’s body, thought to be the border on a wrap-over warrior jacket of the type depicted on the Sutton Hoo helmet.

Walton Rogers, P, 1998, ‘The swordbeater’ in G. Drinkall and M. Foreman, The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Castledyke South, Barton-on-Humber (Sheffield Excavation Reports 6), Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield, pp292-294, 375.

A socketed iron blade from a woman’s burial, originally thought to be a spearhead, has been re-identified as a weaving batten or swordbeater. The spear-shaped form of beater is well known in Scandinavia, but in Britain has often been confused with spears.

Walton Rogers, P, 1998, ‘Cotton in a Merovingian burial in Germany’, Archaeological Textiles News 27 (Autumn issue), 12-14.

A Z-spun thread used to quilt a padded wool diamond twill in a woman’s burial at Lauchheim-Ostalbkreis in Baden-Württemberg proved to be spun from cotton. This is a late 5th-century grave and there is no risk of mis-identification or contamination.

1997

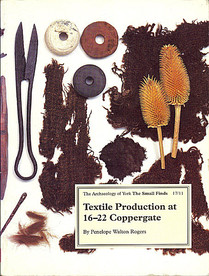

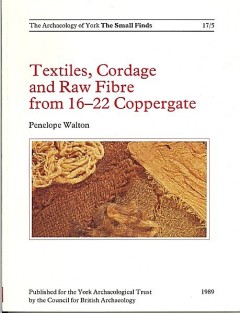

Walton Rogers, P, 1997, Textile Production at

16-22 Coppergate, (The Archaeology of York 17/11). York.: CBA for York Archaeological Trust.

This monograph describes the evidence for textile production recovered from the York Archaeological Trust excavations in Coppergate, and is a companion to the volume on the textile products published in the same series (1989, see below). The raw materials and textile tools are described craft-by-craft, from wool and flax preparation, through spinning, weaving, dyeing and soft-finishing, to cutting, stitching and laundering. Two-thirds of the material belongs to the Viking Age, although most of the evidence fits easily within the native Anglo-Saxon tradition. The shifting pattern of production over the 9th to 13th centuries is described, along with the role of women in the industry, trade in textiles, the rise of the urban gilds and the late medieval trade in raw wool.

Walton Rogers, P, 1997, ‘Late Iron Age textile and fibre remains’, pp110-1, ‘Textile remains’ [from Anglo-Saxon cemetery], 291ff, in A.P. Fitzpatrick, Archaeological Excavations on the Route of the A27 Westhampnett Bypass, West Sussex, 1992, 2: The Late Iron Age, Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries (Wessex Archaeology Report 12), (pub. Wessex Archaeology, Salisbury).

Mineral-preserved ZS twill and animal pelt, possibly cattle hide, were found with metal objects from the Iron Age cremation burials. Remains of a spear-wrapper were found in the nearby Anglo-Saxon cemetery.

Rogers, P, and Taylor, G, 1997, untitled article on dyes, appended (pp83-4) to D C Gluckman ‘Wrapped in paradise: a brief early history of the Kashmir shawl and its decoration’ (pp78-83), Orientations, April 1997 issue.

Analysis of the dyes in 27 yarn samples from eight Kashmir shawls has shown that the insect dye, lac, had been used for all the reds and pinks and was sometimes tinted with indigo/woad for purplish shades. Four different dyes were used for yellows. A note by G.Taylor, on Chinese dyes, was attached to another article in the same issue, p63.

1996

Walton Rogers 1996, P, ‘Dyes and wools in textiles from Slusegård’, in J-H Bech, L Bender Jørgensen, P. Walton Rogers, J. Trier, B.J. Sellevold, V. Alexandersen & T Trolle-Lassen, Slusegårdgravpladsen IV: Keramikken, Tekstilerne, Skeletterne, DE Braendte Knogler, Taenderne (Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskabs Skrifter XIV, 4, Aarhus Universitetsforlag 1996), pp135-140.

Samples from 23 textiles dated to the Roman Iron Age were analysed. Hairy Medium dominated the fleece-types in textiles thought to be native products and Generalised Medium the ‘Virring-type’ textiles. Some of the textiles had been patterned with in naturally pigmented wools, while some of the white wools had been dyed.

1995

Walton, P, 1995, ‘An ivory weaving tablet from York Minster’ in D Phillips and B Heywood, Excavations at York Minster Vol.1: From Roman Fortress to Norman Cathedral (London: RCHME/HMSO), pp428-429.

A small triangular ivory plate from late Roman levels at York Minster has the typical perforations and wear-pattern of a weaving tablet. Other examples from Roman Britain are discussed, although no examples of their products, three-hole tablet-woven bands, have as yet been recovered.

Walton Rogers, P, 1995, ‘The raw materials of textiles from northern Germany and the Netherlands’, Probleme der Küstenforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet, 23, pp389-400.

Pigmented wools, representing brown, grey and black fleeces, were most commonly used for 7th- to 10th-century textiles from North German and Dutch sites. They were mainly primitive types of fleece, classified as Hairy or Hairy Medium and matched the raw wool staples from the same region. Dyes were rare. The analysis helped identify likely imports, which were made from dyed white wool. Includes a small amount of data from earlier and later periods and a glossary which gives the technical definition of individual fleece-types. The textiles from which the samples had been taken were reviewed by Klaus Tidow in the same volume.